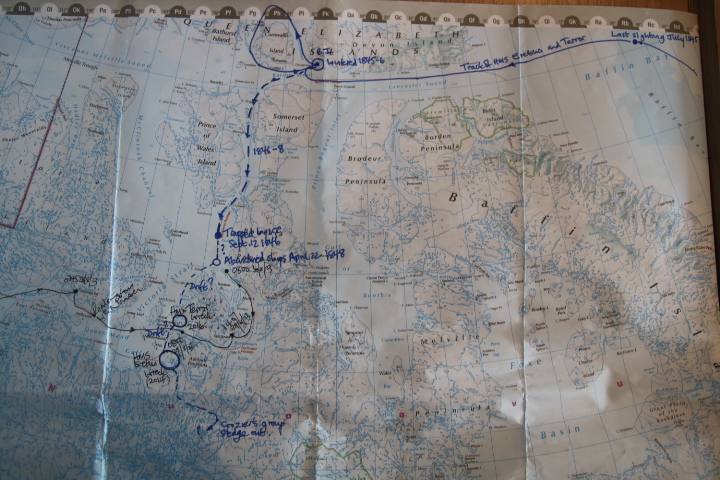

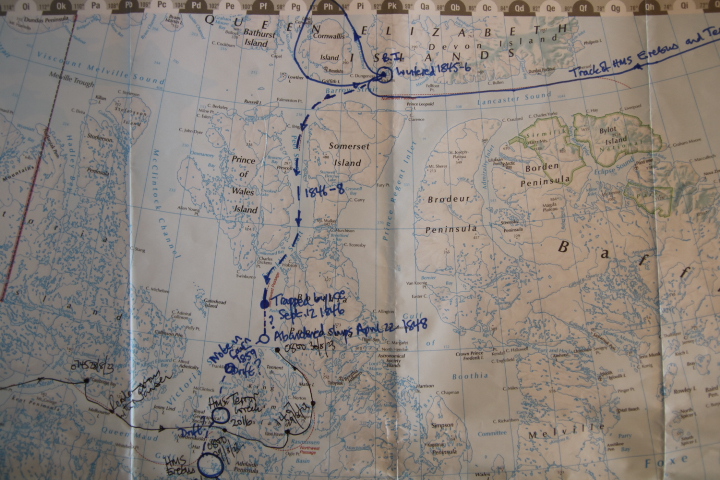

At this stage of the transit, we are at the centre of the Franklin Expedition of 1845 controversy. Overnight we travelled to 69N 95W.

Where we are, in 1845, was the location of the last chance for the British Admiralty to ‘conquer the Far North’. There were a reducing number of supporters for big ventures because of so many failures. However, the ideal ships were apparently to hand. The Erebus and Terror had just returned from Antarctica. These heavily strengthened ships represented the ‘heavy’ approach to conquering the ice rather than the lighter vessels of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Reading the academic texts of this period one can detect a touch of ‘historical hindsight’ because the knowns and unknowns of Arctic exploration were still uncertain, despite numerous attempts, most of which ended in failure or at the best were ‘not quite what we expected’.

During the morning we made good progress to Pasley Bay. We passed the site of Amundsen’s winter camp, where he determined in 1904 the location of the Magnetic North Pole. In the days long before GPS it was important to know the deviation between the Magnetic North Pole and the true North Pole because they are not the same place. Without this knowledge one can be many tens of miles off course by relying simply on the compass, which reflects the magnetic field of the Earth. Until recently this was still being updated.

As we enter Pasley Bay we have travelled 2,200 nautical miles and are not even halfway through the voyage. A landing was planned here but the fog descended and prevented this, because the landing site must always be visible from the ship.

Larsen came here in 1940 – 42 and made slow progress to Pasley Bay. “Sometimes there was not a drop of water in sight as the ice packed itself tightly around us.” By the end of 1941 he had met the full force of the ice pouring down the McClintock Channel and recorded that “we nearly lost the ship – the force of the wind and snow made it impossible to see.” In August 1942, Larsen escaped and sailed past the location of the entrapped Erebus and Terror of the Franklin expedition, but these ships had sunk well before his arrival. He went on to say, “I believe that had we missed the opportunity to get out of Pasley Bay we most probably would be still right out here, in small bits and pieces.”

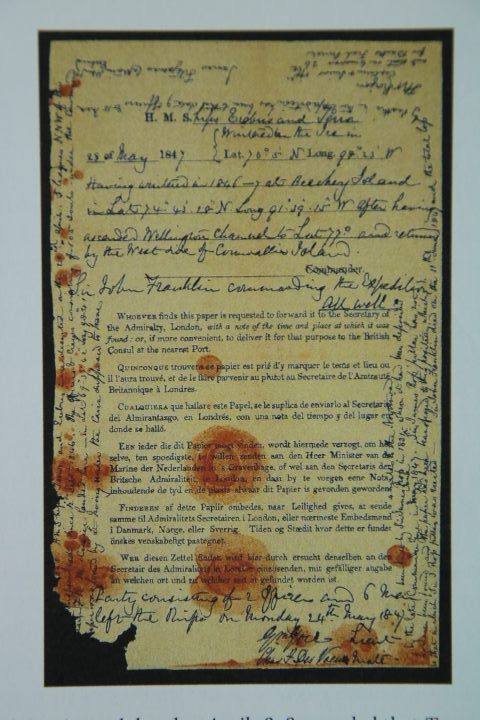

It is off King William Island that the two ships of the Franklin Expedition became entrapped, and it is presumed that all members of the crew were lost in this region.

Searches for the expedition were launched in 1850. In 1854 the Scottish fur trader, John Rae, working for the Hudson’s Bay Company was familiar with overland trade so approached the region overland from the southwest and spoke to Inuit people. It is through these encounters that he supplied the account of dozens of white men dying at what is now named Starvation Cove. It is thought by many historians that Rae is most likely to have been the first to navigate the Passage, but his report to the Admiralty was discredited by them and leaked to the Times newspaper, who published the shocking revelations of cannibalism amongst the surviving crew. This debate continues with the author J. B. Latta claiming this was a conspiracy that covered up and betrayed Franklin as a means of hiding the Admiralty’s intransigence to accept help and advice from indigenous people.